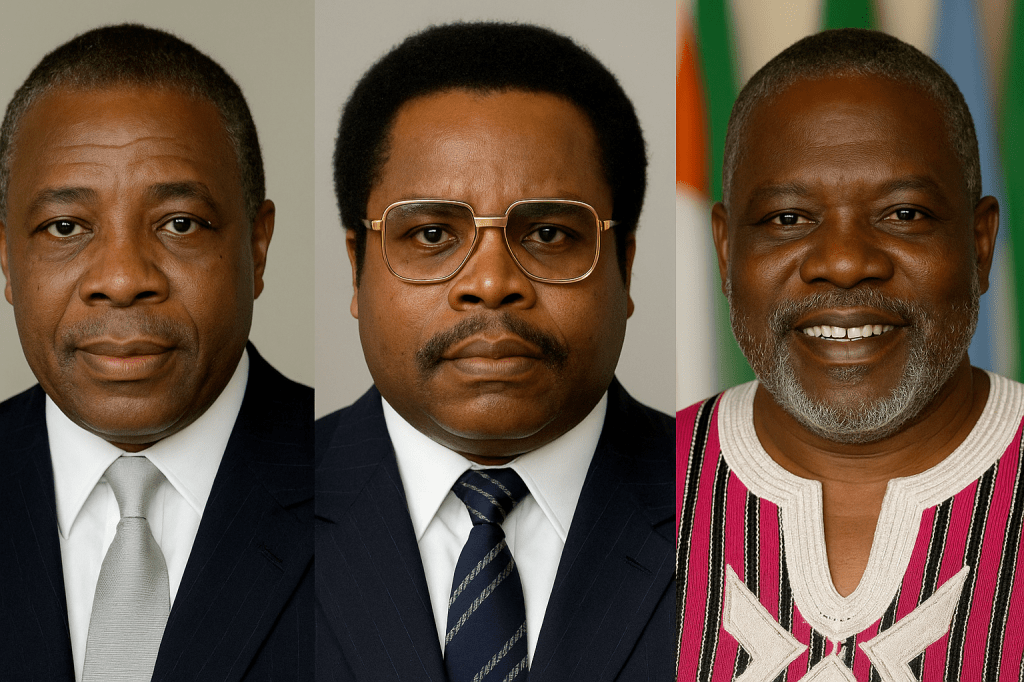

Liberia’s descent into civil war began as a story of three ambitious men locked in a bitter triangle of vengeance, fear and political opportunism. Samuel Doe, a 28-year-old Master Sergeant from the Krahn minority, shattered a century of Americo-Liberian dominance when he murdered President William Tolbert in the 1980 coup. Having seized the Executive Mansion, Doe ruled through patronage and raw coercion, packing the army and security services with fellow Krahn while silencing Gio, Mano and other communities he suspected of disloyalty. His 1985 “election” produced comic-book vote totals and extinguished any hope that Liberia might reform peacefully; by the late 1980s, rice riots, torture chambers and a shrinking economy had left much of the country primed for revolt.

One of Doe’s protégés was Charles Taylor, a shrewd, American-educated Gola who briefly ran the General Services Agency until he was accused of stealing nearly a million dollars. Taylor fled to the United States, escaped from a Massachusetts jail while awaiting extradition, and resurfaced in Côte d’Ivoire. There, with the tacit blessing of President Félix Houphouët-Boigny, he assembled the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), trained fighters—many Gio and Mano driven into exile by Doe—and on Christmas Eve 1989 crossed the border into Nimba County. Taylor sold the venture as a liberation crusade but his real goal was absolute power; diamond fields, timber concessions and a future seat in the Executive Mansion glittered in his mind.

Prince Yormie Johnson, a fiery Gio former army sergeant, entered the story as Taylor’s top battlefield commander. Charismatic yet volatile, Johnson soon chafed under Taylor’s autocratic style and suspicion that loot was being hoarded at NPFL headquarters. By mid-1990 he broke away to create the Independent NPFL (INPFL), instantly turning a single rebellion into a fratricidal contest for Monrovia itself. In September that year, Johnson’s men ambushed President Doe at the outskirts of an ECOWAS peacekeeping compound, sliced off his ears and filmed his death—an act that decapitated the regime but deepened Liberia’s nightmare. With the symbolic enemy gone, Taylor and Johnson turned their guns on each other and on any community deemed Krahn or loyalist; massacres in Duport Road, St. Peter’s Lutheran Church and scores of villages testified to the new logic of revenge.

Ethnicity supplied the fuel. Doe’s earlier persecution of Gio and Mano civilians had primed entire counties to welcome Taylor’s column as avengers. Taylor, in turn, depicted every Krahn man, woman and child as a Doe collaborator, legitimising wholesale slaughter. Johnson’s INPFL exploited the same grievance, portraying Doe’s capture as ethnic justice. Yet ethnicity alone cannot explain the viciousness. Each warlord saw Liberia as a prize and its resources—diamonds in Lofa, timber in Grand Bassa, foreign aid in Monrovia—as personal revenue streams. While they preached patriotism, they bartered logging concessions to French and Malaysian companies, swapped diamonds for Kalashnikovs, and trafficked children into their militias because it was cheaper than paying adults.

Religion hovered only at the margins. The vast majority of Krahn, Gio and Gola rebels identified as Christians, yet fighters carried talismans and “country medicine” charms they believed could turn bullets into water. Taylor occasionally quoted scripture to foreign journalists, styling himself a Christian David against Doe’s Goliath, but his real catechism was profit. Churches and mosques, however, became sanctuaries for civilians and later platforms for peace. The Liberia Council of Churches and the Inter-Religious Council repeatedly convened cease-fire talks, shamed commanders who pillaged sacred sites, and after the guns fell silent opened trauma-healing centres that helped thousands of former child soldiers re-enter society.

By 1997, war-fatigued Liberians calculated that electing Taylor president might at least quiet the guns. He won with 75 percent of the vote, the slogan “He killed my ma, he killed my pa, but I will vote for him” capturing the bleak bargain of the hour. Peace proved illusory. Taylor exported mayhem to Sierra Leone through the Revolutionary United Front, traded “blood diamonds” for arms, and crushed dissent at home. A new insurgency—a motley coalition called LURD—ignited a second civil war in 1999; by 2003 Taylor faced U.N. sanctions, U.S. naval intimidation off the coast and rebels shelling Monrovia. He fled, was later handed to a U.N. Special Court, and in 2012 was sentenced to 50 years for aiding atrocities.

Prince Johnson reinvented himself yet again, swapping his camouflage for a business suit and winning a senate seat for Nimba County in 2005. In televised hearings of Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission he wept, prayed, and refused to apologise for Doe’s murder. Samuel Doe had been dead for fifteen years but his Krahn followers, many now widows and amputees, watched incredulous as their tormentor became a kingmaker in national politics.

Liberia’s first civil war killed roughly 150,000 people, its second perhaps another 50,000; both wrecked an economy that had once out-paced much of sub-Saharan Africa. The spark was Samuel Doe’s dictatorship, the accelerant Charles Taylor’s ambition, the detonator Prince Johnson’s vendetta. Their intertwined lusts for power, money and revenge pulled an entire nation into the abyss and left scars still visible in Monrovia’s bullet-pocked skyline, in the amputee wards of JFK hospital, and in the uneasy coexistence of Krahn, Gio, Mano and Gola communities struggling to believe that tomorrow can be different from yesterday.

Leave a comment