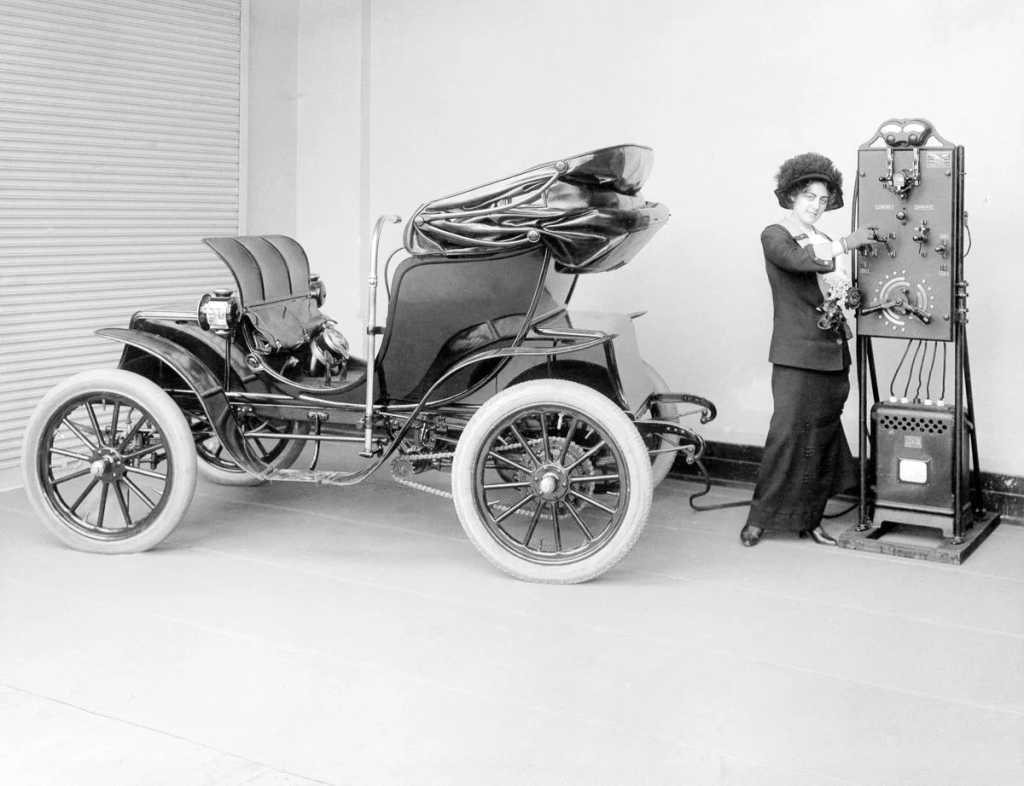

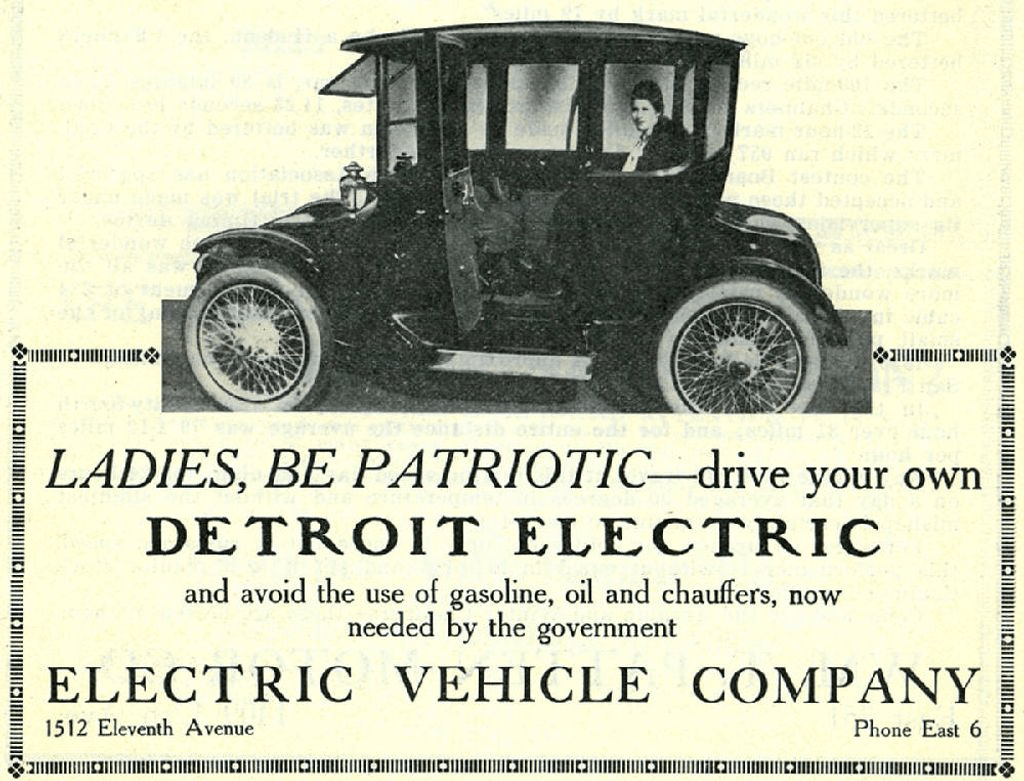

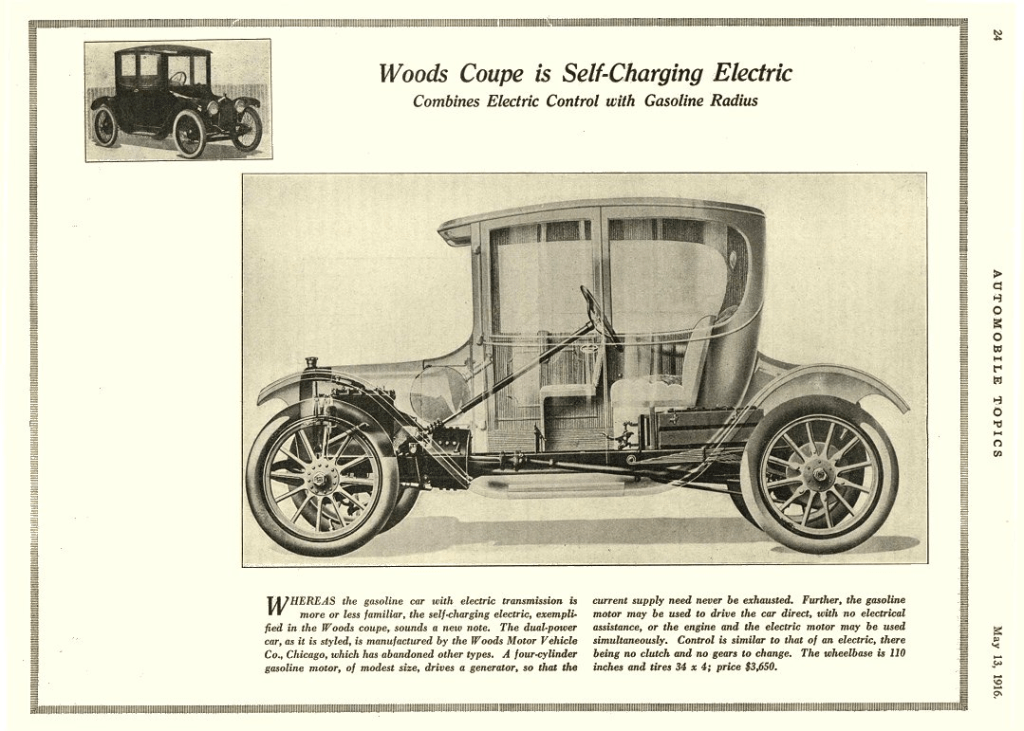

Electric vehicles (EVs) are often seen as a modern solution to climate change and fossil fuel dependency, but few realize that they were among the first automobiles ever built. In fact, by 1900, electric cars accounted for roughly a third of all vehicles on American roads. They were quiet, clean, easy to operate, and required no hand cranking—making them especially popular among city dwellers and upper-class women. Companies like Baker Electric, Columbia, and Detroit Electric were producing sophisticated models capable of 30 to 50 miles per charge, which was sufficient for the urban travel of the time. Early motorists preferred them to the noisy, temperamental, and smoke-belching gasoline engines that often had to be started by hand.

Gallery: Museum of Innovation & Science Collections

The shift from electric to gasoline vehicles didn’t happen overnight; it was a gradual takeover driven by several intersecting forces. Henry Ford’s Model T, introduced in 1908, revolutionized automobile production through mass manufacturing, cutting costs so sharply that gasoline cars became affordable to the average American. Around the same time, the invention of the electric starter in 1912 eliminated the biggest inconvenience of gasoline cars—the manual crank. Meanwhile, vast discoveries of crude oil in Texas, Oklahoma, and California made gasoline cheap and abundant, while electricity was still limited in rural areas where car ownership was growing fastest. Roads were being extended into the countryside, but charging infrastructure remained confined to major cities. Combined with the limited range and speed of the batteries of that era, these developments made gasoline vehicles more practical and economically viable.

Yet, beyond these technical and economic realities, there were powerful industrial interests that shaped the future of transportation. As the oil industry expanded, so did its influence on policy, infrastructure, and public perception. Oil and automobile companies invested heavily in refining, pipelines, and nationwide gas stations, creating a self-reinforcing network that favored internal combustion engines. Once that infrastructure was in place, gasoline cars became more convenient, while electric vehicles were increasingly marginalized. The political power of the oil lobby helped ensure that tax incentives, subsidies, and early transportation policies tilted toward petroleum rather than electricity. Over time, the cultural narrative of mobility itself was redefined—gasoline cars came to symbolize freedom, adventure, and modernity, while electric vehicles were portrayed as slow, delicate, and impractical.

A more modern echo of this dynamic can be seen in the controversy surrounding the nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) battery patents in the late 1990s. These large-format batteries were a promising technology for electric cars, but the patents were controlled by companies with ties to the oil industry, limiting their commercial use for years. Many EV advocates have cited this as an example of how entrenched interests can delay innovation to protect existing markets. It’s not the only case of corporate maneuvering influencing technology adoption, and it lends some weight to the broader idea that electric transportation faced not just technical barriers, but active resistance.

However, while the “EV suppression” theory remains popular, it’s important to separate myth from documented history. There is little direct evidence of a coordinated conspiracy in the early 20th century to destroy electric vehicles. The decline of EVs was largely a product of the technology of the time—limited battery capacity, poor charging infrastructure, and the rapid rise of cheap gasoline. At the same time, it’s undeniable that the success of the oil and automobile industries created systemic biases that sidelined electric alternatives for decades. In other words, the story isn’t one of a single secret plot but of intertwined industrial, technological, and cultural forces that made internal combustion the global default.

The irony is that electric vehicles never truly disappeared—they simply waited. As climate change, urban pollution, and fuel volatility became impossible to ignore, new battery chemistries and digital control systems brought EVs back to life. The 21st-century resurgence of electric mobility is not a new invention but a revival of a century-old idea that was once ahead of its time. Governments now offer incentives, charging networks are expanding rapidly, and major automakers are racing to electrify their fleets. Still, the same structural challenges that once buried EVs linger today: the political influence of the fossil fuel sector, uneven access to infrastructure, and public misconceptions about electric technology.

The history of electric vehicles is ultimately a story about how innovation interacts with power. Technology alone doesn’t decide the future—economic systems, industrial interests, and public imagination do. The early electric cars of 1900 showed what was possible, but their promise was overshadowed by a world built around oil. More than a hundred years later, as the world transitions toward sustainable transport, we are finally rediscovering what those early inventors already knew: that the clean, quiet, and efficient electric car was never a fantasy—it was the future, waiting for its moment to return.

Leave a comment